“Our hope is to leave behind a sustainable, profitable business that will make a lasting impact on the lives of both the local farmers and the employees, giving them a sense of security and confidence by providing them with a regular, dependable income.”

Sam Gill was born in the US but he and his two older brothers grew up in Bolivia where both his parents were born. When Sam was a baby his parents along with his two older brothers lived in Sumatra for two years. While he has no memory of these days, his parents filled several albums with many pictures which Sam has always enjoyed looking at as well as listening to his brothers and parents retell stories from their time there. This left a lasting impression on his life.

Even though he was a US citizen, Sam never felt like he belonged in the US, particularly as he grew into an adult. The bulk of his childhood was spent in Bolivia, seeing abject poverty first-hand. While Sam was a boy his parents modeled a life spent serving others rather than purely living for oneself.

“A life lived for oneself is so much less meaningful than a life spent for the good of others. I wanted to experience that as an adult and make a difference somehow”, says Sam.

Where better to start a community development project than in Indonesia? Sam and his wife, Julie, moved to Indonesia as newlyweds in 2011. (Since then, they have added three children to their family.)

Before working with coconuts, Sam looked into various options, including distilling clove oil and starting a cocoa plantation. A friend, Jeremy Hicks, had already set up a DME VCO Unit near Madjene, West Sulawesi, so Sam paid him a visit.

“Jeremy was very gracious in allowing me to learn from his experience. When I saw a DME unit in action and started to understand what it would entail, I began to gain confidence that I could start up a similar operation in South Sulawesi.”

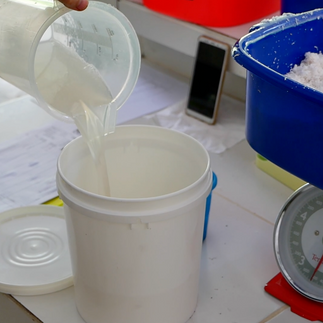

Of all the options for beginning a sustainable community development business, pressing Virgin Coconut Oil (VCO) began to look the most promising. Kokonut Pacific’s DME unit would require a relatively small capital investment, which made it very attractive. Also, the skills needed to be successful in operating a DME unit do not require a higher education. There was already a market for all the coconut by-products which meant that the business would be much closer to sustainability from the start.

Additionally, as an added personal bonus for Sam’s family who enjoy open space, starting a DME unit meant they could move out of their dense urban setting into the rural village of Calinrung, near a small river.

It took about eight months to complete the factory, with several interruptions. In total there was about five months of actual construction work. “We had a party on 28 December 2018 with the locals to celebrate its completion.”

Now, just a few years on, the drier, while still working well, is starting to develop lots of cracks and may need serious repair in a few years time. In hindsight Sam is convinced that heat resistant cement, though considerably more expensive, would have been the better way to go to prevent this from happening.

Initially production was low, only 700ml per batch, partly due to the variety of coconuts that the team was using and partly due to their inexperience in proper drying technique. The grated coconut was not dried evenly which affected the yield after pressing. Additionally, it is difficult to tamp the grated coconut into the cylinder when it has not been dried evenly. It took about a month for the team to become proficient in drying which in turn has resulted in higher yields and a cleaner, clearer oil everyone is proud of.

Another challenge was the terms of employment. New structures and hours had to be adopted to suit local customs and culture. For example, if someone in the village has an accident or if there is a funeral, all work stops out of respect. It’s a constant juggle to establish a workplace that is productive and efficient while managing the cultural norms. Sam is currently learning the local language which has proven to be of tremendous help.

At certain times through the year supply of coconuts is limited. Locally, everyone plants and harvests at the same time. For example in January/February all the land with coconut palms have corn growing under them and no one harvests coconut until the corn is picked. This means paying a premium for coconuts to come from further away. For many parts of the Pacific, coconuts can be picked all year round. Here in South Sulawesi, for those who do intercropping in the coconut gardens, picking of the coconuts is often seasonal. To add to this challenge, currently the Copra market has pushed up the price of coconuts.

“Despite the challenges, we are so grateful to have come this far, now on the verge of having a sustainable business model that also contributes to the well-being of the locals."

We are also thankful that the initial suspicion has melted away, and we have become an accepted part of this community. They know they can trust us, both because of the integrity with which we conduct the business and because of the way that we share our lives with them.

One of the things that we would like to leave with the people is a deep appreciation for education and innovation. As with just about all new technology, the DME method of VCO extraction is the result of hard science and a willingness to experiment. Often, especially in very old cultures, innovation and change are looked at with a great deal of suspicion. While change can certainly be harmful, it is also possible to be very helpful. We want people here to see the DME method as an example of what can happen when someone is willing to study, experiment and innovate. Understanding how the laws of physics work (or other facts about the world around us) can make us become better equipped to deal with the challenges that we face in life.

Comments